Positional Encodings of Attention Mechanisms: Sinusoidal, Rotary Positional Encodings (Part 2)

If you missed it, please check out part 1!

They were standing under a tree, each with an arm round the other’s neck, and Alice knew which was which in a moment, because one of them had ‘dum’ embroidered on his collar, and the other ‘dee.’ ‘I suppose they’ve each got “Tweedle” round at the back of the collar,’ she said to herself.

- Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There

Poor Alice is plagued by the inverted rules of the world inside the looking glass when she meets Tweedledee and Tweedledum. The only saving grace of her encounter with another path down ad absurdum is that they had their names on their collar. Otherwise mirror images of each other, Tweedledee and Tweedledum never contradict each other but speak in different contexts (‘contrariwise’) for the same content. Alice even tries to create an order between the two, labelling one as ‘first boy’, and the other ‘next boy’, but this doesn’t go down well. Eventually, she shakes both hands at once in case she offends the other by shaking one of theirs first.

They aren’t the same being but two distinct entities that carry the same content with different contexts. Without their names on their collar, it would be impossible to distinguish between Tweedle dee and dum. Still, thankfully Lewis Carroll wasn’t cruel enough to present us with a world without positional encoding, and it’s recorded that ‘Alice knew which was which in a moment’.

Recall from the previous post that by the definition of a ‘sequence’, each element in it should have the following two properties:

- have a reason behind its location within the sequence

- some feature(s) must provide the trichotomy(which produces an order)

In the domain of Attention models, we decided that either adjusting the attention scores with some positional information or enhancing the value representation with awareness of its position was the way to go. (refer to part 1)

In this post, let us figure out how we can actually do that so that Tweedledum and Tweedledee will never be confused again.

Positional Encoding

Position is both an absolute and relative concept, and representing such a notion with numbers is challenging. The simplest way of encoding position is what Alice has done. You name each sequence position or explicitly state the order of things. With numbers, that would mean assigning each item its index in the sequence. The index can be added/concatenated to the original input vectors, which would change the sequence’s scores/value representation.

While this satisfies the uniqueness of each item and provides a relative reference of distance between the positions, there needs to be a suitable encoding when the sequence length becomes longer and longer. The numerical value that encodes the position will become larger and larger compared to the rest of the data and will eventually skew the model. The typical answer to this is normalisation, like we would do with a neural network’s input/layer outputs. However, normalising it min-max means that the positional information depends on the sequence length. That would mean the positional information between two sequences of different sizes would be different at the same index.

So before we move on to thinking about other ways to encode position, let us define some functional properties the positional encoding should have:

-

Order: This is self-explanatory, but a positional encoding should be able to provide an order between the positions.

-

Uniqueness: Each position should have a unique representation.

-

Relative and Continuous: The representation should be relative to the other positions in the sequence. i.e. the distance between two positions should be well-defined.

-

Invariance: The encodings should be invariant to the sequence length.

-

Purpose: It should either affect the scores of the attention mechanism, the value, or both.

While finding a single number representation that satisfies the above properties may be possible, it becomes clearer that using a vector representation gives us more flexibility. We are already familiar with a positional notation that uses a list of numbers to represent a single value, the base-2 numeral system, or simply binary numbers. These positional notations have digits that rotate over their base/radix value, and their rank increases to accommodate bigger numbers.

These are useful as rotating numbers over their radix means that the relative difference between positions is uniform and satisfies all the other qualities we want. Yet these types of positional encodings are not continuous, and it’s hard to represent them as an injective and continuous function of the element index of a sequence. It’d be better to use a continuous function that takes in the element’s index and outputs a discretised vector representation of the position.

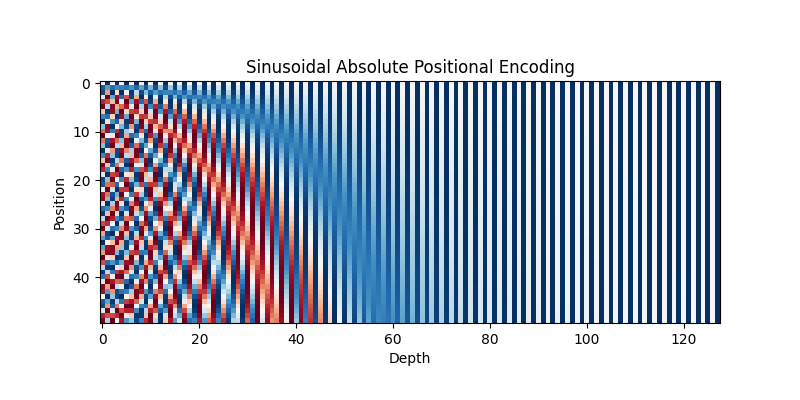

Following suit with the ‘rotating numbers’ idea, the original authors of the ‘Attention is all you need’ paper decided to use the sine function. The binary representation of the index has alternating zeros and ones but at different periods for each dimension, making them unique. This periodicity with varying periods seems to have naturally led the authors to the sine function with a monotonically increasing period over the dimensions. i.e. creating a vector with the form:

\[PE_{i, j} = sin \left( \frac{1}{\omega^{j/d_{model}}} \ i \right)\]where $i$ represents the index of the sequence, and $j$ is the dimension of the positional encoding vector. $j/d_{model}$ varies between 0 and 1. The first dimension of the positional encoding vector will have a minimum period of $2\pi$ radians, and the last dimension will have a maximum period of $\omega * 2\pi$ radians. The authors set $\omega$ as $10000$, probably a choice made after experimentation. Anywhoos, perfect! It satisfies all the things we’ve discussed above.

It handles its purpose by having the length of the positional encoding vector set to be the same as the dimension that the rest of the model uses. The positional encoding vector is added to the input, so the resulting query, key, and value will all have positional information injected into them. Before we move on, though, let’s think about the following.

Positional encoding was introduced to solve the problem of invariance between a sequence and its permutation. To achieve this, we’ve discussed that the (key, query) pair should carry some positional information, or the value should be different per location. Considering the (key, query) pair case, what’s important is their relative positional difference(i.e how far is the key from the current query). That means it would be super helpful if there were a way for the positional encodings to know how far they are from each other without depending on their absolute position.

To rephrase the question, can we get $sin \left( \frac{1}{\omega^{j/d_{model}}} (n+ \phi)\right)$ from $sin \left( \frac{1}{\omega^{j/d_{model}}} n\right)$, for position $n$ and positional difference $\phi$?

I mean, there is the compound angle formula

\[sin(n+\phi) = sin(n)cos(\phi) + cos(n)sin(\phi)\]and it kinda works, but given that formula, if we consider using pairs of sine and cosine instead of just sines. We can simplify it to:

\[\left( \begin{matrix} cos(n + \phi) \\ sin(n + \phi) \end{matrix} \right) = \left( \begin{matrix} cos(\phi) & -sin(\phi) \\ sin(\phi) & cos(\phi) \end{matrix} \right) \left( \begin{matrix} cos(n) \\ sin(n) \end{matrix} \right)\]And it becomes conceptually appealing as a different position can be expressed by applying a linear transformation called a ‘rotation’ applied to a given position.

It isn’t explicitly stated why they use pairs of sine and cosine in the original paper, but they do mention that by doing so you can “attend to relative positions since $PE_{pos+k}$ can be represented as a linear function of $PE_{pos}$”

The final positional encoding vector is as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} PE_{i, 2j} &= sin \left( \frac{1}{\omega^{2j/d_{model}}} \ i \right) \\ \\ PE_{i, 2j+1} &= cos \left( \frac{1}{\omega^{2j/d_{model}}} \ i \right) \end{aligned}\]Pairs of sine and cosine with the same period are used, and the period monotonically increases as you go down the dimension in pairs.

Rotary Positional Encoding - RoPE

Now that we’ve covered the properties of positional encoding with the example of the original absolute sinusoidal scheme above, let us explore other derivations of said qualities.

As shown in the previous section, the gist of it all is to have an understanding of relative positional differences. Relative encodings are based on creating a pairing of positions in the sequence and then encoding the relative difference between them. The pairing is typically expressed with a $N$ x $N$ matrix between positions, which might not work with efficient transformer implementations. The point is there needs to be a more principled approach to coming up with these encodings, and Rotary Positional Encoding(RoPE) is one of them. Alice only needs to know Tweedledum is the boy to the left of Tweedledee and vice versa, not their absolute position.

The author of RoPE creates a constraint on the inner product of the query and key that incorporates relative positional information.

We want to find a positional encoding function $f(\mathbf{x}, l)$ for token $\mathbf{x}$ and its position $l$ such that for two items $\mathbf{x_q}$ and $\mathbf{x_k}$ at positions $m$ and $n$, it satisfies the following:

\[\left < f(\mathbf{x_q}, m), f(\mathbf{x_k}, n) \right > = g(\mathbf{x_q}, \mathbf{x_k}, n-m)\]The inner product between two position-encoded vectors should only depend on the original vectors and their relative positional differences. The inner product of the position encoded vectors is the score function, and it makes sense to only depend on the original token values and their relative positional difference. Shifting the query and key position by the same amount will change their absolute position but not the relative positional difference, so the inner product should be the same.

We need to find a function that allows for the dot product in the attention mechanism to have this property: preserving the relative positional information while discarding the absolute position. Recall that the geometric interpretation of the dot product is given as

\[\mathbf{x} \cdot \mathbf{y} = ||\mathbf{x}|| ||\mathbf{y}|| \cos \theta\]where $\theta$ is the angle between the vectors. Borrowing the idea of using pairs of sine and cosines from the previous section, if we can represent the positional information as rotations applied to the vectors, it satisfies the preservation of relative differences. If the same angle rotates both vectors, their dot product won’t change. So RoPE focuses on changing the key and query of the attention mechanism to produce a better score representation.

To find the function that maps the positional information to rotations, we first change our view of the token vector to be a vector of complex numbers made with pairs of the original vector. That is, we view

\[\mathbf{x_q} = (x_{q1}, x_{q2}, \dots, x_{qd}) \in \mathbb{R}^d\]As

\[\mathbf{x_q} = (x_{q1} + ix_{q2}, x_{q3} + ix_{q4}, \dots, x_{qd-1} + ix_{qd}) \in \mathbb{C}^{d/2}\]In this representation, the positional encoding functions become:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x_q}, m) &= R_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)}e^{i\Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)}} \\ f(\mathbf{x_k}, m) &= R_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, n)}e^{i\Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, n)}} \\ g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, n-m) &= R_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, n-m)}e^{i\Theta_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, n-m)}} \\ \end{aligned}\]The inner product with this representation yields the following equations:

\[\begin{aligned} R_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)}R_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, n)} &= R_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, n-m)} \\ \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)} - \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, n)} &= \Theta_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, n-m)} \end{aligned}\]This is from the fact that given two complex numbers $z_1$ and $z_2$, the inner product is given by $z_1 \cdot z_2 = |z_1||z_2| \cos(\theta_1 - \theta_2)$ where $\theta_1$ and $\theta_2$ are the angles of the complex numbers.

By setting some intial condition $f(\mathbf{x}, 0) = \mathbf{x}$, we notice that

\[R_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, 0)}R_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, 0)} = R_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, 0)} = \mathbf{x_q}\mathbf{x_k}\]If $R_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, 0)} = \mathbf{x_q}\mathbf{x_k}$ Then for all $m = n$ we have that $R_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)}R_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, m)} = \mathbf{x_q}\mathbf{x_k}$ as well as $m-m = 0$

This means that $R$ is indpendent of the position $m$, and ths we can imply say $R_{f(\mathbf{x}, y)} = \mathbf{x}$ for all position $y$.

Similarly, by setting the initial condition $\Theta(\mathbf{x}) = \Theta(\mathbf{x}, 0)$, we have:

\[\Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, 0)} - \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, 0)} = \Theta(\mathbf{x_q}) - \Theta(\mathbf{x_k})\]Utilising the same logic as the $R$ case, we can see that $\Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)} - \Theta(\mathbf{x_q}) = \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, m)} - \Theta(\mathbf{x_k})$ for all $\mathbf{x_q}$, $\mathbf{x_k}$. It doesn’t depend on the query or key. Denoting $\Theta_{f(x, m)} - \Theta(x)$ as $\varphi(m)$, we have the following useful representation of $\Theta_{f(x, m)}$:

\[\Theta_{f(x, m)} = \Theta(\mathbf{x}) + \varphi(m)\]Plugging this in to the original equation with m = n+1, we have:

\[\begin{aligned} \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_q}, m)} - \Theta_{f(\mathbf{x_k}, m+1)} &= \Theta_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, 1)} \\ &= \Theta(\mathbf{x_q}) + \varphi(m) - \Theta(\mathbf{x_k}) - \varphi(m+1)\\ \\ \varphi(m+1) - \varphi(m) &= \Theta_{g(\mathbf{x_q},\mathbf{x_k}, 1)} + \Theta(\mathbf{x_q}) - \Theta(\mathbf{x_k}) \\ \end{aligned}\]Interestingly, the RHS of the equation does not depend on $m$ and thus $\varphi$ must also not depend on $m$, rendering it down to an arithmetic progression. If we set initial values $\varphi(0) = 0$ and $\varphi(1) = \theta$, where $\theta$ is a step rotation amount to be decided, we have $\varphi(m) = m\theta$

Plugging this back into the original equation, we have:

\[\Theta_{f(x, m)} = \Theta(\mathbf{x}) + m\theta\]We now have all the ingredients to write the positional encoding functions in the complex form:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x_q}, m) &= R_{\mathbf{x_q}}e^{i(\Theta(\mathbf{x_q})+ m\theta)} \\ &= ||\mathbf{x_q}||e^{i(\theta_q + m\theta)} \\ &= ||\mathbf{x_q}||e^{i\theta_q}e^{im\theta} \\ &= \mathbf{x_q}e^{im\theta} \\ \\ f(\mathbf{x_k}, m) &= R_{\mathbf{x_k}}e^{i(\Theta(\mathbf{x_k})+ m\theta)} \\ &= ||\mathbf{x_k}||e^{i(\theta_k + m\theta)} \\ &= ||\mathbf{x_k}||e^{i\theta_k}e^{im\theta} \\ &= \mathbf{x_k}e^{im\theta} \\ \end{aligned}\]We have a positional encoding function that takes in the token vectors and gives us an encoded version that, when dot-producted with another encoded vector, will preserve the relative positional difference.

To use it, it’d be best to change the view to the real version. As an intuitive example, let us reduce the problem down to the 2d case where

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{x_q} &= (x_{q1}, x_{q2}) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \\ \mathbf{x_q} &= (x_{q1} + ix_{q2}) \in \mathbb{C} \end{aligned}\]Here, applying the positional encoding function will look like the following.

Recall the positional encoding function:

\[f(\mathbf{x}, m) = \mathbf{x}e^{im\theta}\]Expand the exponential using Euler’s identity:

\[f(\mathbf{x}, m) = \mathbf{x}e^{im\theta} = \mathbf{x}(cos(m\theta) + isin(m\theta))\]Applying this function to the 2D case will look like:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\mathbf{x_q}, m) &= (x_{q1} + ix_{q2})e^{im\theta} \\ &= (x_{q1}+ ix_{q2})(cos(m\theta) + isin(m\theta)) \\ &= x_{q1}cos(m\theta) + ix_{q2}cos(m\theta) + ix_{q1}sin(m\theta) - x_{q2}sin(m\theta) \\ &= x_{q1}cos(m\theta) - x_{q2}sin(m\theta) + i(x_{q1}sin(m\theta) + x_{q2}cos(m\theta)) \\ \end{aligned}\]The real and imaginary parts of the complex number represent a pair of dimensions in the original ‘real’ case. We can see that the positional encoding function modified the initial token vector as:

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} x_{q1} \\ x_{q2} \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} x_{q1}cos(m\theta) - x_{q2}sin(m\theta) \\ x_{q1}sin(m\theta) + x_{q2}cos(m\theta) \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]This can be written as a matrix multiplication as well:

\[\begin{bmatrix} x_{q1} \\ x_{q2} \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} cos(m\theta) & -sin(m\theta) \\ sin(m\theta) & cos(m\theta) \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_{q1} \\ x_{q2} \end{bmatrix}\]This is precisely the rotation matrix we were talking about earlier! We managed to represent positional information as rotations applied to vectors!

We can generalize this to the $d$-dimensional case by applying the above to each pair of dimensions of the token vector.

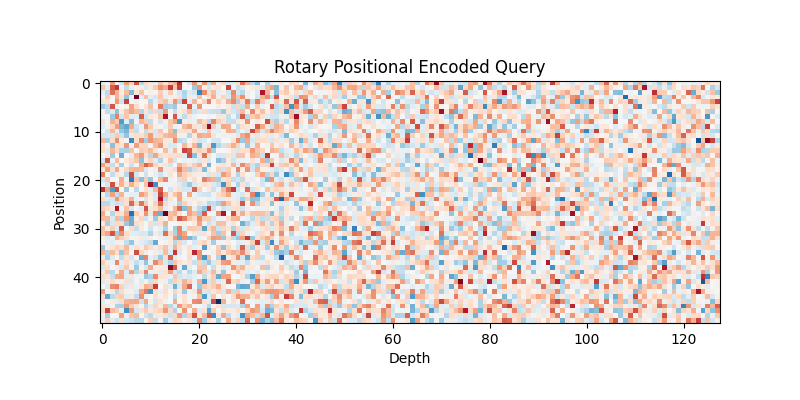

This may seem similar to the absolute sinusoidal positional encoding function, but it is not. The absolute sinusoidal positional encoding function is a function only of the token’s position in the sequence.

In contrast, the relative positional encoding function is a function of the query/key representation of the token and the position of the token in the sequence. On top of this, while the fixed absolute positional encoding is added to the token vector, RoPE is multiplied based on the first-principle derivation we went through above.

The Rotary Positional Encoding idea has seen a lot of success in many Pre-trained Language Models and is generating quite a buzz in the Chinese NLP community. There are more and more implementations of PLTs with RoPE, and I believe we’ll see more of them in the future.

What I like about RoPE is that it formulated the problem of positional encoding in a principled manner, allowing us to see why this might work and how this has come to be. It wasn’t even that far off from the original functions the authors of ‘Attention is all you need’ used. Approaches with strong foundations like this is not usually seen in the deep learning community, where telltales of experiment results are often used to justify the design of a model.

“No, no!” said the Queen. “Sentence first— verdict afterwards.” “Stuff and nonsense !” said Alice loudly. “The idea of having the sentence first !” “Hold your tongue!” said the Queen, turning purple. “I won’t !” said Alice. “Off with her head !” the Queen shouted at the top of her voice.

Comments