Positional Encodings of Attention Mechanisms: Weighted Sums and Attention(Part 1)

Check out part 2!

Introduction

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely Players;

They have their exits and their entrances…

Ever have that feeling when you stop and simply perceive the world around you, then become awe-struck at its beautiful orchestration? I certainly do, and amidst the frustration in attempting to describe that exact impression, you somehow find wisdom in Shakespeare’s words.

The monologue in ‘As you like it’ presents us with a perspective we can take advantage of. If the world is a stage and everything in it are actors, the feelings must come from two things: the mise-en-scène of the stage and, more prominently, the interactions of the players within that scene.

In mathematical language, the former is paralleled with the constraints, definitions, and assumptions we make for the model. The interactions would be composed of the following:

- Interactions between different actors or with oneself, denoted by the multiplication of variables(or values derived from variables)

- The relative strength between interactions given as ratios/weights/coefficients (that are multiplied to the variables)

- Scaled/gated/convolved resultant values of interactions through function compositions

So at the risk of over-simplification, the language of description is a series of well-structured multiplications and additions. This framework helps abstract the dynamic and complex nature of our view of the stage. Yet, without a strict understanding of specific properties that we’d like the model to respect, the information enclosed within the context of weighted sums can become ambiguous.

How do you infer distinct meanings from each of the interactions represented with additions and multiplications?

Maybe an opinionated mise-en-scene can enforce a specific rule; perhaps the actors can carry a particular identifier by wearing a tag on their arm, and so on. There isn’t one definite answer to this, but many. In this post(especially in part 2!), we’ll look at how various authors injected specificity in a sequence’s order as they direct a play called sequential phenomena(natural language).

Neural Networks

Neural networks are a family of models that are widely used to represent higher-order tasks and problems. The premise is that we define an event we want to describe with the data it generates. Then, by iteratively fitting the data to a pre-defined function, we hope that the fully converged model produces a similar distribution to the trained data. In doing so, two things need to happen. First, the model structure needs to be defined, and then the model weights and biases must be updated via gradient descent against an objective function.

The model is made up of layers that compute the weighted sum of the inputs, which is then passed through a non-linearity to create the output. Technically, you can use whatever shape or form to express a problem(as long as the input and output dimensions match your problem description and it has at least one hidden layer). However, that’s similar to asking the actors on stage to perform while all wearing similarly coloured costumes with a bare-minimum prop set and a blank background. With a lot of focus and rehearsal, it might just work out, but there must be a better way of doing things.

Let’s revisit the question:

“How do you design a model such that, despite the limited context of weighted sums, manages to capture the key properties of the given data?”*

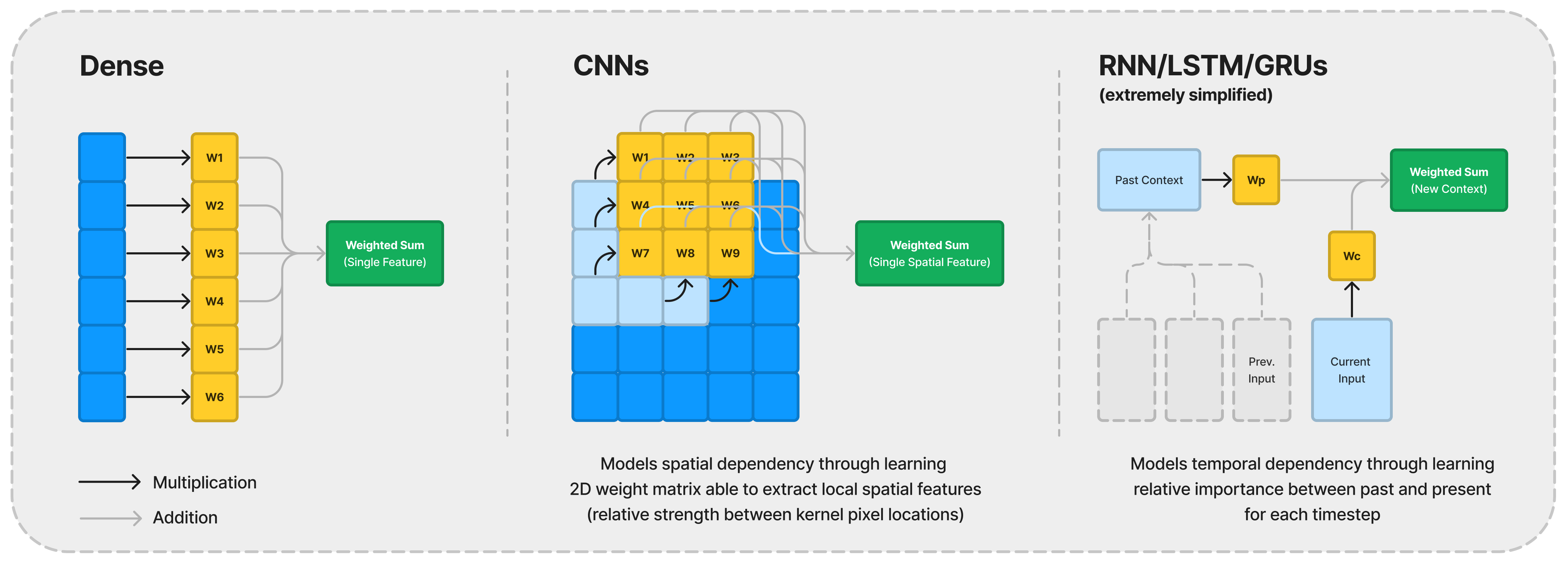

That should be part of our active considerations when implementing a neural network. A successful example is the introduction of Convolutional Neural Networks(CNN) for image data. By utilising the weighted sums in 2D convolution kernels, it’s been shown to better incorporate the spatial dependencies that we expect the pixels to have, compared to flattening the image and then using a dense multi-layer 1D perceptron model. By giving the actors specific cues on where to stand as they interact, the stage is suddenly flowing more naturally, and the true shape of the play starts to emerge more vividly.

In sequential data, the critical property to consider is the ability to utilise past data in the current prediction, i.e. to model the temporal dependency. Recurrent Neural Networks(RNN), Long Short Term Memory(LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Units(GRU) are cases where their formulation helps weigh between the past context to the current input. They eventually boil down to structures that produce learned weights representing the suitable ratio of what to forget and what to remember between the past and present at the current timestep.

Like these examples, mathematical modelling, including neural networks, is all about capturing the interaction happening on stage with multiplication, addition, and composition/convolution. In doing so, we build instructions that portray the fundamental properties we want to extract.

Attention

Weighing between past contexts and present data is limited in the sense that as the sequence length increases, information from earlier timesteps becomes more and more diluted. On top of it, the auto-regressive nature of it means you need to parse the sequence steps one by one, which can be computationally expensive. Why not use the entire sequence as a whole? Attention mechanisms exploit that exact notion.

According to Wikipedia, a sequence is “a … collection of objects in which … order matters”. The term ‘order’ tacitly carries two attributes we naturally hold in our minds. An element appearing at a specific position must have a reason behind its location, and some feature(s) must provide the trichotomy(not just by numerical magnitude, but in an abstract sense) necessary for an ‘order’ to emerge. If we were to paint a scene that describes some sequential event, these two attributes would be the primary view we’d want it to stand out.

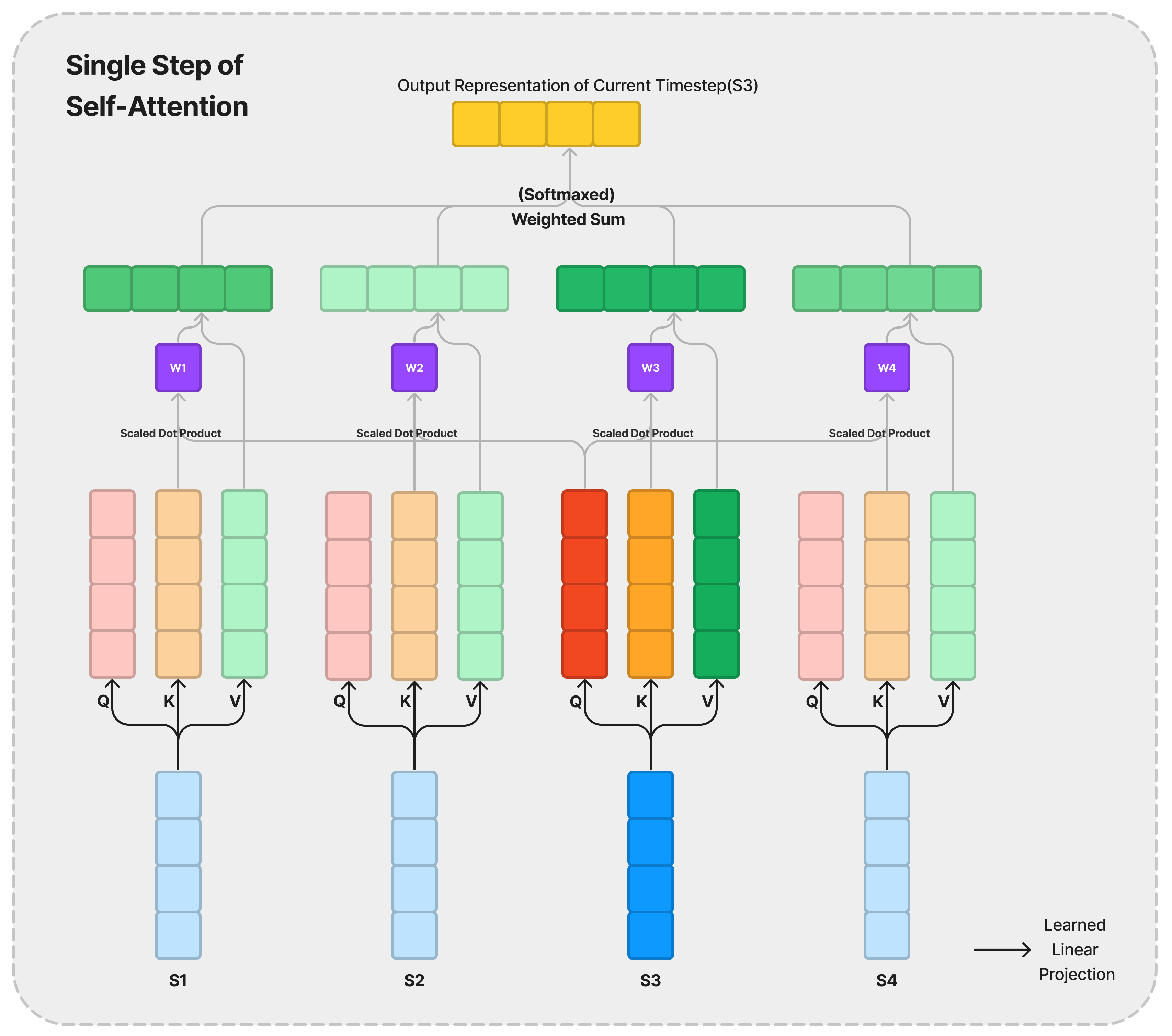

Attention layers do that by creating weights for each element in the sequence and by transforming the input into a ‘value’ that (hopefully) is more distinguishable as a distillation of features.

The final representation of the current timestep is created by summing the value of each element in the sequence, weighted by the attention weights. As the layer is trained, one anticipates that the weights will embody the relative ‘focus’ that the current input is exerting to other locations of the sequence. As we compute the weights of the entire sequence at once, it is also more efficient than the recurrent layers discussed above. The weights are created through a score function, which utilises two other transformations of the input called the ‘query’ and ‘key’.

\[f: \text{query of current timestep, }\{\text{key of each timestep}\} \\ \rightarrow \text{weight of the key timestep to the current input}\]Typically, the ‘query’, ‘key’ and ‘value’ representation of inputs are real vectors, and the scoring function takes the form of an inner product such that it produces a scalar wieght. This blog post series will focus on the scaled dot product between the query and key vectors as the scoring function.

We have a sketch that extracts better features and a way to signify the relative importance between locations. What needs to be added is the ability to distinguish the same input appearing at different locations. For example, given the same input at two different time steps, its query, key and value representations would be the same. This isn’t suitable when we know that ‘there must be a reason behind an element’s location within the sequence’. Recurrent Neural Networks didn’t have that problem as it updates the past context step-by-step, thus inherently utilising the order of the inputs.

Two ways to inject that additional knowledge into the attention model are noticeable right off the bat. Either adjust the score with some sort of positional information (i.e modify the query and keys) or enhance the value representation with awareness of its location. The original authors of ‘Attention is all you need’ adds an absolute sinusoidal vector(with relative properties) to the input to adjust all of the query, key, and value. Others focus on the key and query and their relative distances, and we’ll look at the diverse ways they’ve done it in the next post.

Attention mechanisms are now being used everywhere from Computer Vision, Large Language Models, to Protein Folding Predictions and much more. It’s a powerful tool that is scalable, configurable and easily trainable. The way that the design of it helps encapsulate the essence of what a sequence carries is an example of masterful directorship of a stage so sought after.

All the World’s a Stage, and Attention is all it needs.

The next part of this blog post will dive into the mathematics behind different methods that have been proposed to inject positional information into the attention mechanism. So make sure you check that out too!

Jeehoon

Comments